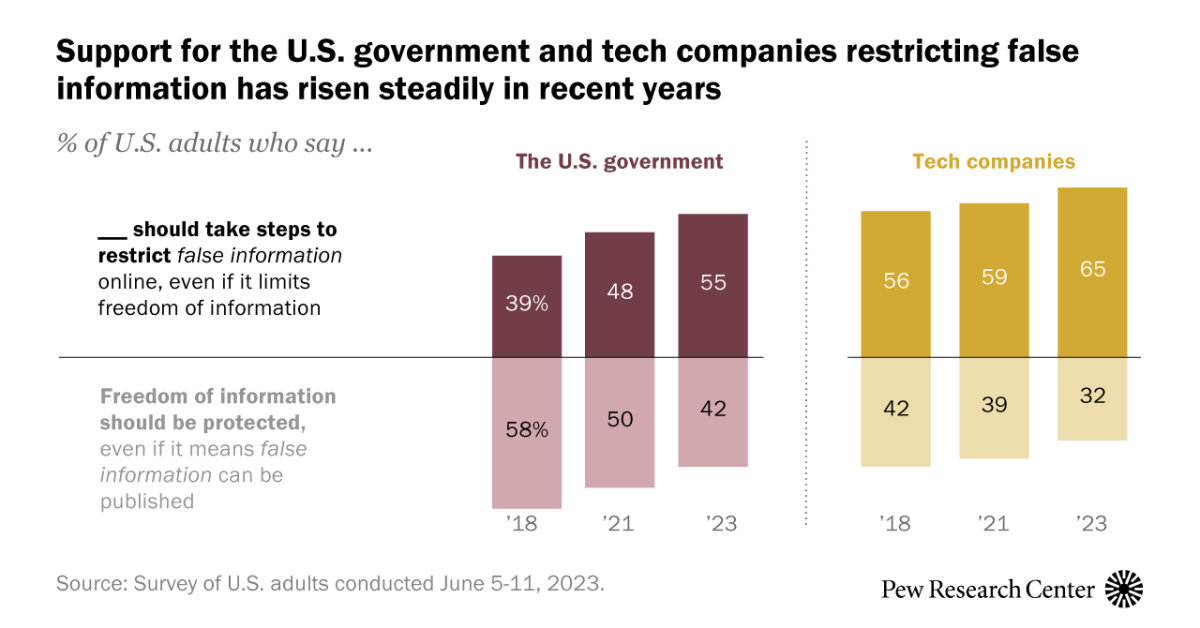

65% of Americans support tech companies moderating false information online and 55% support the U.S. government taking these steps. These shares have increased since 2018. Americans are even more supportive of tech companies (71%) and the U.S. government (60%) restricting extremely violent content online.

Checks out. I wouldn’t want the US government doing it, but deplatforming bullshit is the correct approach. It takes more effort to reject a belief than to accept it and if the topic is unimportant to the person reading about it, then they’re more apt to fall victim to misinformation.

Although suspension of belief is possible (Hasson, Simmons, & Todorov, 2005; Schul, Mayo, & Burnstein, 2008), it seems to require a high degree of attention, considerable implausibility of the message, or high levels of distrust at the time the message is received. So, in most situations, the deck is stacked in favor of accepting information rather than rejecting it, provided there are no salient markers that call the speaker’s intention of cooperative conversation into question. Going beyond this default of acceptance requires additional motivation and cognitive resources: If the topic is not very important to you, or you have other things on your mind, misinformation will likely slip in.

Additionally, repeated exposure to a statement increases the likelihood that it will be accepted as true.

Repeated exposure to a statement is known to increase its acceptance as true (e.g., Begg, Anas, & Farinacci, 1992; Hasher, Goldstein, & Toppino, 1977). In a classic study of rumor transmission, Allport and Lepkin (1945) observed that the strongest predictor of belief in wartime rumors was simple repetition. Repetition effects may create a perceived social consensus even when no consensus exists. Festinger (1954) referred to social consensus as a “secondary reality test”: If many people believe a piece of information, there’s probably something to it. Because people are more frequently exposed to widely shared beliefs than to highly idiosyncratic ones, the familiarity of a belief is often a valid indicator of social consensus.

Even providing corrections next to misinformation leads to the misinformation spreading.

A common format for such campaigns is a “myth versus fact” approach that juxtaposes a given piece of false information with a pertinent fact. For example, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offer patient handouts that counter an erroneous health-related belief (e.g., “The side effects of flu vaccination are worse than the flu”) with relevant facts (e.g., “Side effects of flu vaccination are rare and mild”). When recipients are tested immediately after reading such hand-outs, they correctly distinguish between myths and facts, and report behavioral intentions that are consistent with the information provided (e.g., an intention to get vaccinated). However, a short delay is sufficient to reverse this effect: After a mere 30 minutes, readers of the handouts identify more “myths” as “facts” than do people who never received a hand-out to begin with (Schwarz et al., 2007). Moreover, people’s behavioral intentions are consistent with this confusion: They report fewer vaccination intentions than people who were not exposed to the handout.

The ideal solution is to cut off the flow of misinformation and reinforce the facts instead.